Biden Is Speaking to an America That Doesn’t Exist

Many citizens support the recent attacks on democracy, and those who don’t face a system stacked against them.

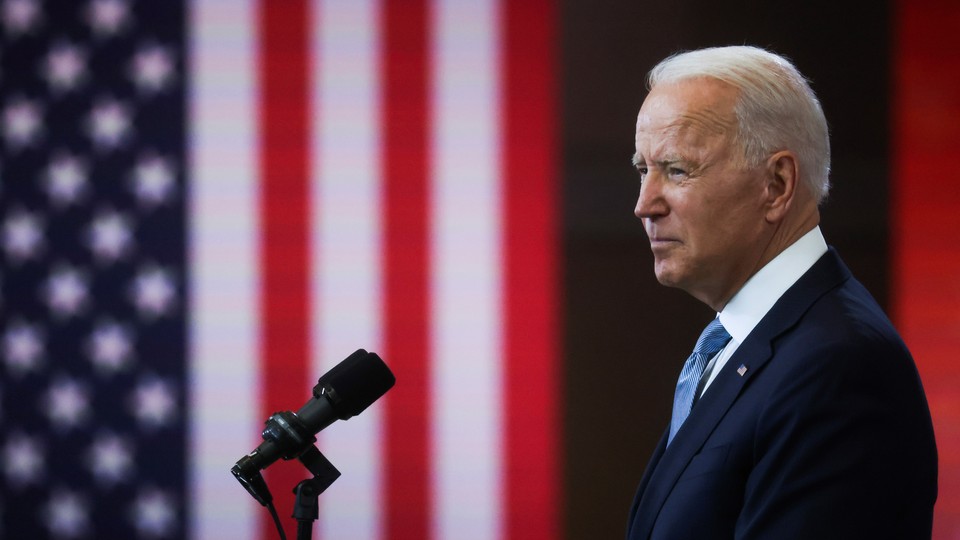

Joe Biden is not known as a fiery orator, but the president was riled up yesterday.

Biden spoke in Philadelphia about voting rights, calling a current round of state laws and bills, plus rhetoric emanating from Donald Trump and others, “the most significant test of our democracy since the Civil War.” The president defended the 2020 election, celebrating the record voter turnout, praising election officials who made sure voting was smooth, and rebutting attacks lodged by Trump and his aides, who have baselessly claimed that the election was stolen or marred by fraud. “No other election has ever been held under such scrutiny, such high standards,” Biden said. “The big lie is just that: a big lie.”

But the president’s main focus was the next election, which he warned was gravely threatened. “I’m not saying this to alarm you,” he said. “I’m saying this because you should be alarmed.” He added, “We have to prepare now.”

The question is, who is we?

Biden’s speech assumes a unified American people who support democratic norms, and it assumes that once they understand the threat posed to those norms, they’ll be willing and able to fend it off. That nation is a chimera. Many Americans support these attacks on democracy, and those who don’t face a system stacked against them.

Biden is right to spotlight the dangers, and he was unusually fervid in making his case. For some time, many states have sought to tighten voting restrictions, including requiring photo IDs to vote or purging infrequent voters from rolls—even though no evidence of fraud on the level to swing elections exists. After many states loosened rules regulating absentee or mail-in voting during the pandemic, a number of legislatures have begun writing laws to roll those changes back. Many of these laws are expected to have a disproportionate impact on Democratic constituencies.

But as Biden said, “It’s no longer just about who gets to vote or making it easier to vote, but who gets to count the votes.” Many state legislatures have passed or are considering laws that would take election administration out of the hands of current election officials at the state level and assign them to more partisan overseers; they have written legislation that targets low-level election officials and makes them subject to penalties for actions such as mailing out unsolicited absentee-voting applications. Some longtime administrators have quit amid threats from legislators and the public, while others continue their work despite intimidation. In some states, lawmakers have tried to give themselves the power to override voters’ preferences under certain circumstances.

The premise of Biden’s speech seems to be that voters will uniformly be troubled by this. “Have you no shame?” he asked Republican officials. By now it should be clear that many do not. And they have cover, because many Republican voters back the changes. Polls find that between two-thirds and three-quarters of GOP voters don’t believe Biden is a legitimate president. Six in 10 Republicans think it’s more important to change laws to prevent fraud (which doesn’t happen) than to make voting easier, according to a recent Washington Post/ABC News poll. At the grassroots level, GOP voters appear to strongly back many of the very things Biden warns against.

As for those Americans who are alarmed, they have scant power to do anything about it—including Biden, who offered little in the way of new ideas. He called for the Senate to pass the For the People Act, a massive voting bill, and the John Lewis Voting Rights Act, but both bills have been stalled by GOP filibusters in the Senate. Biden did not call on Senate Democrats to eliminate the filibuster or create a work-around for these bills, but even if he had, it wouldn’t have done much good; Senators Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema, the Democrats’ 49th and 50th votes in the chamber, have made clear that they oppose any changes.

Unified Republican control in 23 states means that opponents have little chance to derail voter-suppression bills at the state level. In state capitals, the country is witnessing a divergence between Democratic-led states, which tend to be loosening their voting laws or keeping them the same, and Republican-led ones, which are mostly moving to make voting more difficult.

In the past, voter advocates and Democratic administrations have relied on the judiciary to block legislation that makes voting harder for some people. Biden praised efforts by civil-rights groups to “stay vigilant and challenge these odious laws in the courts” and touted an already-announced plan to beef up the Justice Department’s voting-rights team. But those lawyers and their peers in private practice face a system that’s less and less friendly to their challenges; the Supreme Court issued a decision further weakening the Voting Rights Act earlier this month.

Without any real levers left to pull, Biden has only the bully pulpit of the presidency. The problem is that the power of persuasion has always been overstated, and may be weaker today than ever.

And so he proceeds as though the world is otherwise. During his inaugural address, Biden pledged to bring together a divided populace. “I know speaking of unity can sound to some like a foolish fantasy these days,” he said. “I know that the forces that divide us are deep and they are real.” He’s got a lot of work ahead of him on that front, and until it’s complete, he has little choice but to appeal to an America that doesn’t exist.