Thanks to the pandemic, many of us are now familiar with both the benefits and perils of working from home.

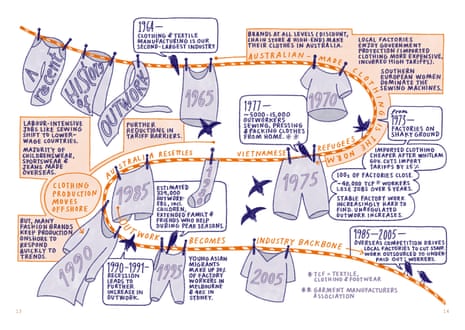

That’s old hat in the garment business: for decades, Australia’s fashion industry has relied upon the labour of outworkers sewing in their lounge rooms, kitchens and sheds. This hidden workforce is mostly made up of new migrants who pick up orders through word-of-mouth referrals.

For Emma Do, a fashion writer who has worked for Frankie and Broadsheet, it was a revelation to discover Vietnamese names and faces behind many well-known brands.

“I was like, wow, Asian people are in fashion in Australia?” she recalls. “I was just used to seeing white designers be the face of everything.”

As she learned more about outwork, she started piecing together memories. She recalls how her best friend at uni once gave her a free Sass & Bide T-shirt, because back in the mid-to-late noughties, while her friend was in high school, her great aunt sewed them as an outworker for the brand (Sass & Bide have subsequently been acquired by Myer, and list their current manufacturing and sourcing policies online).

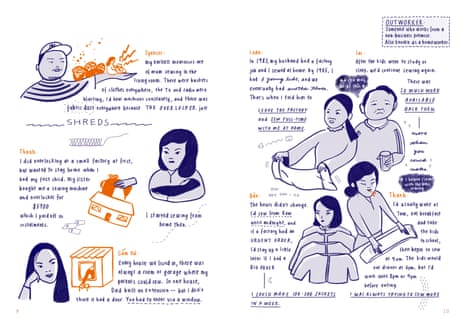

During lockdown, Do paired up with illustrator Kim Lam to create Working From Home, or may ở nhà, a graphic narrative nonfiction book exploring the stories of Vietnamese outworkers past and present. Supported by Creative Victoria, the book was launched in April 2021 with a limited print run. It’s now already gone into its third edition.

Lam’s parents both worked in textile factories, and she was often babysat by outworkers growing up. She remembers the smell of machine oil, cold rooms with concrete or tiled floors (so it was easier to sweep away loose fibres), with SBS Vietnamese or Paris by Night playing in the background. Once, she bumped her head, and an aunty pressed her cold sewing scissors to her forehead in lieu of an ice pack.

For many new migrants, particularly women, outwork offers an opportunity to make money while juggling parenting and care responsibilities at home. Often the work becomes a family affair.

“My husband would help, and even my daughter would help trim,” recalls Nguyet Nguyen, who worked from home as a machinist for over 20 years, starting in the late 80s when her daughter was little. She’d learned to sew back in Vietnam, and she didn’t want to send her daughter to childcare.

Now a textile, clothing and footwear industry organiser with the CFMEU manufacturing division, Nguyet has been part of historical changes in the industry that have improved conditions for outworkers.

Instead of being paid per piece as contractors, Australian outworkers are entitled to hourly rates based on garment estimation, as well as superannuation, sick leave, annual leave, and all the other award conditions that on-site employees receive.

That significant win came in 2012 and could perhaps be a lesson for today’s gig economy: the food delivery industry has been in the spotlight recently, accused of exploiting migrant workers classed as contractors; while on farms, reports say that piece rate payment has resulted in some workers making less than $2 per hour.

“Our industry was one of the first to experience sham contracting,” says Beth Macpherson, the CFMEU’s national compliance officer for textiles, clothing and footwear. “Hopefully the structure that we have developed is something other industries can rely on.”

Despite these major changes to the textile industry award, Macpherson says illegal and exploitative practices do sometimes persist. “Companies know they’re doing the wrong thing, but they think no one will ever find out because the worker is hidden and can’t speak English.”

Union organisers encourage local businesses to undergo auditing and accreditation through Ethical Clothing Australia to show that they are committed to paying and treating workers fairly. Internationally, labour rights advocates are urging big brands to recommit to binding agreements such as the Bangladesh Accord, which is set to expire at the end of August.

For Do and Lam, it’s important to draw attention to labour rights, but also to stress that exploitation is not the only story. Though many of their outworker interviewees were modest about their achievements, they also took pride in their skills, their stoicism and their contribution to fashion.

“There’s dignity in being able to make something out of nothing,” says Lam.

If there’s one thing she would like fashion lovers to remember, it’s that every garment is the result of human labour.

“All clothes are handmade. They’re not churned out by machines. They’re all made by a person – even the Kmart ones.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion