‘Cyber seed’ that ‘grows like a plant’ could revolutionise how we design vehicles, medical equipment, and more

The ‘seed’ grows algorithmically in a CAD environment - and while the outcomes are random now, researchers say it could develop incredibly quickly

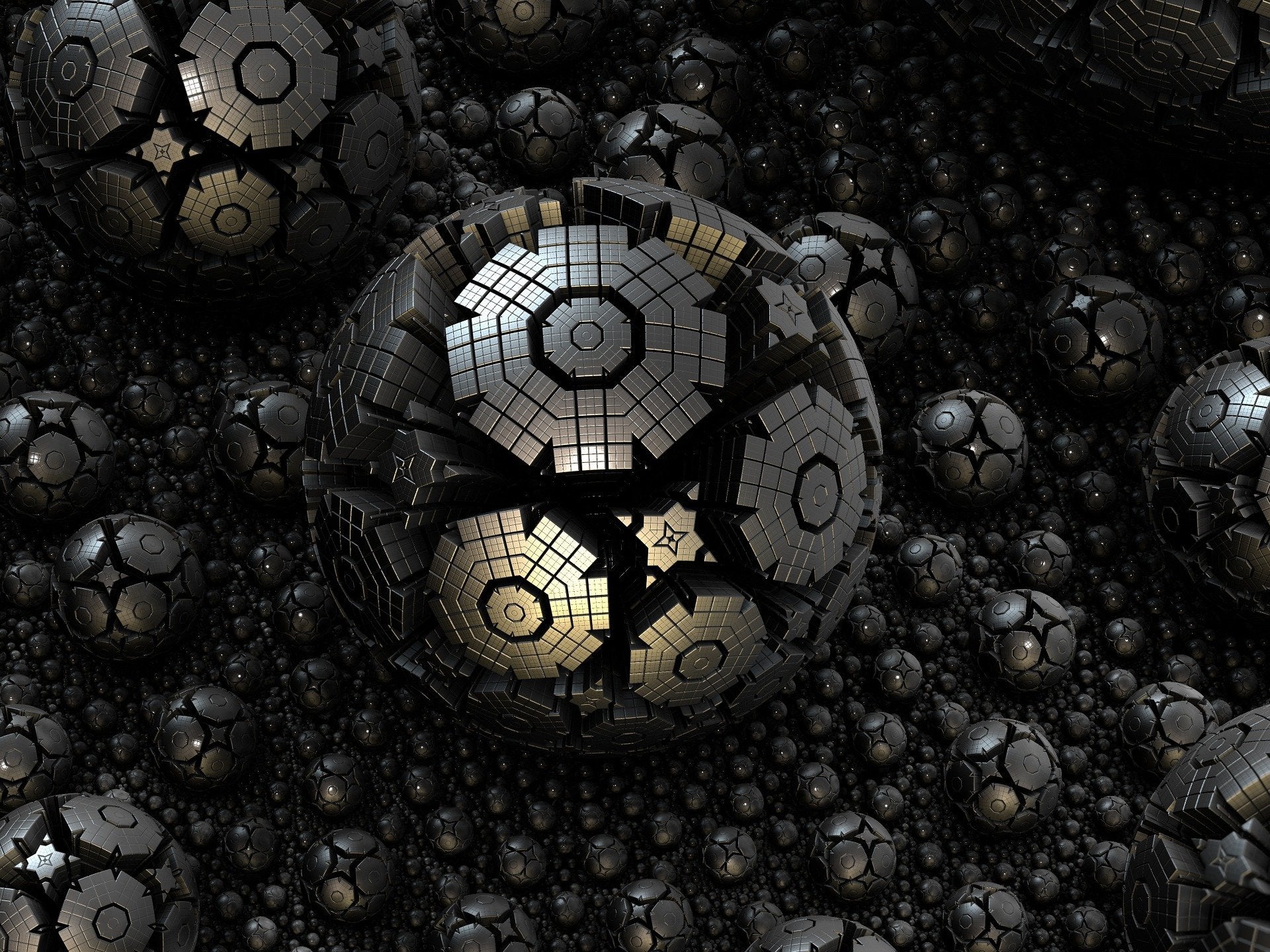

A ‘cyber seed’ that grows ‘like a plant’ to design structures using material from the local environment has been developed by researchers.

The ‘seed’ is composed of hundreds of pieces of information, digitally encoded, that includes data on necessary materials, properties, and other parameters such as weight, height, colour, and density. Simple seeds could have 50 lines of information, with six pieces of information per line.

This seed, algorithmically, then attempts to grow into a particular design set out by researchers from Queen’s University Belfast, Loughborough University and the University of York.

Starting off from a single cell in a CAD (computer-aided design) program, the seed will grow in a certain direction until it reaches the limit of the parameter it has been programmed with.

A 10cm-square, for example, could grow until it reached a particular length, at which point the algorithm would direct it to a new behaviour – like computer programs that develop fractals from a series of simple rules, but creating defined objects rather than infinite repetitions. Currently, the results can look random, but eventually they will become more ordered, and more useful to humans.

“This cyber seed grows within a computer model just like a stem on a plant does in nature - it gets longer and longer as it grows”, Professor Mark Price said.

“The seed generates cells which divide and copy to build up very complex shapes but they only become viable when they meet certain conditions, in the same way nature works.”

As the ‘seed’ grows, it will eventually reach a ‘bud’, which is when it will change its behaviour to account for artificial sensors to grow, for example, handlebars or pedals.

A seed for a bicycle in Belfast, for example, could develop the vehicle using metal with the result made of aluminium; that same seed in Mumbai, in contrast, would develop using bamboo as its main material and adapt its design accordingly. They could also, eventually, be linked to manufacturing machines through the cloud and products can then be made locally on demand.

Eventually, this development could be used to algorithmically generate designs for a great number of vehicles and aircrafts, Professor Price told The Independent – although currently, the seed is limited in what it can achieve. Attempts to generate a wall bracket resulted in several designs that, while unsuitable, are a step forward in the development of the program.

Currently the program is being used to try and develop simple designs for structures such as scaffolding, simple engineering structures that are significantly less complex than bicycles or aircrafts. It is also possible that the ‘seed’ could have knowledge of its environment, and therefore ‘grow’ against a wall or other barrier, accounting for boundaries as it develops.

The researchers have not yet attempted a design for more difficult objects, such as gears, but Professor Price told The Independent that he is confident this program could be used to design a working, manufacturable frame within five years, and the complete airframe for an airship within two decades.

The ‘seeds’ right now are run through an artificial evolutionary process, where hundreds of designs are created and ran through a computer program that will select the beneficial designs.

That takes a serious amount of computing power – a desktop computer could run the program in a couple of hours, but a high-performance parallel computing cluster could achieve it in seconds. When more sophisticated designs are needed, the researchers will need to simulate for environmental constraints such as structural integrity, air flow, temperature, electromagnetism, and so on, which can be very expensive.

But one of the long-term benefits of the ‘seed’, Professor Price told The Independent, is that it could also find designs that humans might never have considered.

“We do lots of things under commercial pressure and regulatory frameworks, so you do the thing that is good and safe and reliable”, he said, “but because this is not constrained by the same things, it will throw up very different ideas.”

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies