The Rich, Weird, and Frustrating World of Depression-Era Travel Guides

The American Guides were unusual not only for their shaggy opulence and Americana maximalism, but also for their source of funding: the federal government.

Imagine stopping someone on a Manhattan street and asking for directions to Times Square. If that person launched into a monologue beginning, “It is the district of glorified dancing girls and millionaire playboys and, on a different plane, of dime-a-dance hostesses and pleasure-seeking clerks. Here, too, in a permanent moralizing tableau, appear the extremes of success and failure characteristic of Broadway’s spectacular professions: gangsters and racketeers, panhandlers and derelicts, youthful stage stars and aging burlesque comedians, world heavyweight champions and once-acclaimed beggars,” and then that person recounted the history of every theater and club, the development of the area’s rapid public transit, and the origin of the phrase “the Great White Way” (coined, supposedly, in 1901 by the adman O. J. Gude), all in a tone both disdainful and celebratory of the famed intersection that “lights the clouds above Manhattan with a glow like that of a dry timber fire”—you would know what it was like to read the American Guides, a curious series of books that appeared during the last years of the Great Depression. Specifically, you’d know what it was like to read the New York City Guide, which was published in 1939. And you’d be no closer to Times Square.

Alongside New York City, there was a guide for every state (48 of them then), plus the District of Columbia, the Alaska Territory, Puerto Rico, many cities and towns, locales such as Death Valley, and routes such as U.S. 1. The public bought them, expecting concise and functional travel companions. But the hefty American Guides were something else.

These books sprawled. They hoarded and gossiped and sat you down for a lecture. They seemed to address multiple readers at once from multiple perspectives. Most were divided into three sections. First, perplexed readers paged through essays on history, industry, folkways, and other subjects. Then came profiles of notable cities and towns, and finally, a collection of automobile tours across the state. The tours highlighted scenic overlooks and recreation spots, but also infamous massacres, labor strikes, witches, gunfighters, Continental Army spies, Confederate deserters, shipwrecks, slave rebellions, famous swindlers, and forgotten poets. They traveled through towns with bizarre names and towns founded by religious cults. They paused for every old-timer’s story that could be fastened to a patch of ground. They mentioned all the places where Washington ever slept (or so it seemed). They included research on subjects of little use to a traveler (the structure of local government, a state’s literary residents) but barely noted diners, motels, and gas stations. They were rich and weird and frustrating. They guided tourists across the land but also deep into the national character, into a past that was assembled from the mythic and the prosaic, the factual and the farcical. The tours seemed less accessories for motorists than rambling day trips through the unsorted mind of the republic.

This shaggy opulence, this Americana maximalism, made the guides unusual. But their provenance made them remarkable. They weren’t issued by some erratic publisher or obsessive tourist association: They were created by the federal government through the Federal Writers’ Project, a division of the New Deal’s Works Progress Administration. The American Guides were among the unlikeliest weapons in the improvised arsenal that the Roosevelt administration brought to bear upon the Depression.

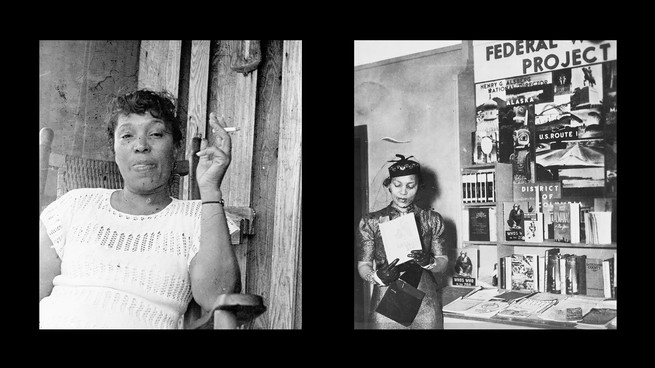

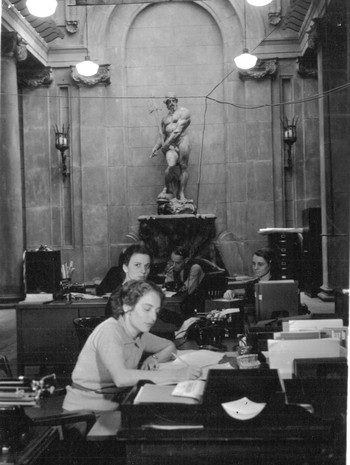

Launched soon after the formation of the WPA in 1935, the FWP provided work for unemployed writers, whether professional or aspiring, competent or otherwise. The program wasn’t huge, comparatively. The entire WPA employed more than 2 million people a month, on average, while the FWP typically had 4,500 to 5,200 workers and peaked at 6,686, all scattered in offices around the country. They came from a range of professions: mostly white-collar workers whose jobs had disappeared and who were better suited to desk labor than, say, draining malarial swampland, along with poets and novelists, including some significant writers whose fame had been eclipsed by the Depression and others who had yet to become famous. (Richard Wright and Zora Neale Hurston were among those who collected an FWP paycheck.)

The FWP was a work-relief program, and its primary mission was to help writers survive the Depression, while putting cash into circulation and contributing, however modestly, to the economic recovery. But it was also a literary endeavor of unprecedented scale. When the FWP was finally dissolved, along with the rest of the WPA, in 1943, Time magazine gave it the epitaph “the biggest literary project in history”—a claim that does not seem to be disputed.

The project might have been a disaster. Many doubted that staffing an unwieldy government bureaucracy with temperamental and often desperate writers—not a few impaired by heavy drinking, professional jealousy, political sectarianism, or all three—could lead to any good outcome. (The journalist Dorothy Thompson remarked, “Project? For Writers? Absurd!” and the poet W. H. Auden, unknowingly echoing Thompson, later called the entire WPA arts program “one of the noblest and most absurd undertakings ever attempted by a state.”) But from 1937, when the first guides appeared, to the project’s end, the FWP managed to produce at least 1,000 publications and gather reams of unused material. (Some of these manuscripts, especially individual life histories and the testimonials of formerly enslaved people, would be treasured and interrogated by future scholars.) Each successful publication chipped away at assumptions about the FWP, proving that it was no hopeless boondoggle for failed writers and unimaginative hacks. Reviewers were generally impressed, finding that the books far surpassed their expectations. The guides seemed, in their own odd and beguiling way, to represent a distinct aesthetic achievement.

The critic Alfred Kazin ended his book On Native Grounds—written contemporaneously with the FWP—by taking up the “literature of nationhood” that had emerged most forcefully after the crash of 1929. As Kazin described it, this genre comprised an upsurge of disparate writing “whose subject was the American scene and whose drive always was the need … to chart America and to possess it.” Edmund Wilson’s book of reportage The American Jitters fit this pattern by issuing dispatches from the great national unraveling. So did You Have Seen Their Faces, a documentary record of the southern poor, written by Erskine Caldwell and photographed by Margaret Bourke-White, which forced an introduction between its readers and their often-overlooked fellow citizens. Books such as these had literary ancestors in Ralph Waldo Emerson, who struggled to conjure up a distinct and meaningful American spirit at his desk, and in Walt Whitman, who chased that spirit down and sought to become possessed by it.

The American Guides epitomized this new literature. Kazin singled them out for praise and insisted on their literary merit (the superior volumes, anyway), perhaps because he knew that they had surpassed the low expectations of so many reviewers. In 1942, the books were still fresh—several had only just been published—but Kazin had a clear view of where they belonged in his story of American literature:

The WPA state guides, seemingly only a makeshift, a stratagem of administrative relief policy to tide a few thousand people along and keep them working, a business of assigning individuals of assorted skills and interests to map the country, mile by mile, resulted in an extraordinary contemporary epic. Out of the need to find something to say about every community and the country around it, out of the vast storehouse of facts behind the guides—geological, geographic, meteorological, ethnological, historical, political, sociological, economic—there emerged an America unexampled in density and regional diversity … More than any other literary form in the thirties, the WPA writers’ project, by illustrating how much so many collective skills could do to uncover the collective history of the country, set the tone of the period.

The American Guides, in other words, could not be dismissed as mere curiosities—or as evidence of the New Dealers’ mania for spending tax dollars in creative ways. The books were key to understanding the historical moment, because the guides, as Kazin put it, had become “a repository as well as a symbol of the reawakened American sense of its own history.”

The guides’ wandering, capacious, and yet startlingly resonant take on the American experience explains why so many people, including myself, have been drawn to these books and the story of how they came to be—how it was that the federal government ended up in the publishing business, with such a peculiar list of titles to show for it. As a historical undertaking and a collective editorial project—created under conditions of enormous strain, at a scale never attempted, by workers grappling with the stresses of poverty and, for many, their own inexperience—the American Guides were a triumph. But the books themselves are not triumphalist. They carry a whiff of New Deal optimism, sure, but for the most part they resist those signature American habits of boosterism and aggressive national mythologizing. As the young novelist Robert Cantwell wrote in The New Republic in 1939, the guides are “a grand, melancholy, formless, democratic anthology of frustration and idiosyncrasy, a majestic roll call of national failure, a terrible and yet engaging corrective to the success stories that dominate our literature.”

Cantwell was right. For books that are ostensibly travel guides, the FWP publications have a habit of wandering off—steering, more often than not, down forgotten back roads and toward the dead ends of American history. But that was the point. The guides do form “a majestic roll call of national failure,” as Cantwell put it, and also more than that. They are melancholic at times, but they are exuberant, suggestive, slapdash, overdetailed, and overconfident too. The spirit of the guides, in other words, is multitudinous and democratic—they have a fundamentally public orientation to match the public enterprise that created them. They don’t offer one way of looking at a state but several. They contain many voices but, as books for travelers, they convey essentially a single invitation to explore, to roam, to inquire.

These books, with their range of perspectives, emerged from the work of a diverse group of writers—some who were among the boldest names in the history of 20th-century American literature and others who never quite escaped the pages of little magazines and obscure manifestos. These writers, whatever their relative renown, labored alongside thousands of others whose contributions are difficult to trace but who made up the majority of FWP workers, the ones who showed up to offices or issued field reports from everywhere in the country. They all experienced life on the project in different, and often totally opposing, ways. They loved the work; they felt like hacks. They saw the FWP as launching their careers; they saw it as a sad and bitter end. Black writers were marginalized, and yet a remarkable group of them produced groundbreaking studies of African American life. Native Americans were also largely excluded as workers in roles across the FWP, though nearly every guide includes references to their history. These passages are typically bundled up with sections about archaeology rather than appearing in essays on the contemporary scene; the guides, in other words, are often guilty of relegating Native Americans to the past rather than portraying them as active participants in the present. The guides themselves, meant to convey an argument about inclusion and pluralism, were sometimes undermined by their own creators—and the compromises of language and of emphasis involved in their creation.

By plucking its workers from all corners of the land, the FWP inevitably became a showcase for their ideas, aspirations, and prejudices. All the tensions of American society in the ’30s were stuffed between the lines of the project’s books and pamphlets. The program was a roiling and seething experiment, and even its participants could not agree on what it all meant: Was it a noble vehicle for progressive patriotism, a fount of radical propaganda, or a bureaucratic instrument for managing social strife and whitewashing history? Was it all of these? The guides don’t provide an obvious answer. Instead, they offer a snapshot of a nation reckoning with urgent questions—about historical progress, the role of government, and the future of democracy itself—at a moment when all the old answers seemed to be dissolving.

This article was excerpted from Scott Borchert’s book The Republic of Detours: How the New Deal Paid Broke Writers to Rediscover America.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.