To Defeat China, Fighter Jet Speed Is Just as Important as Stealth

As the United States reenters the realm of great power competition, America needs to maintain its technological edge in stealth, but would benefit from a renewed emphasis on speed in combat aviation.

As the United States reenters the realm of great power competition, America needs to maintain its technological edge in stealth, but would benefit from a renewed emphasis on speed in combat aviation… even at the expense of observability in some platforms.

For some, the above sentence will read like a ham-fisted oxymoron coming from a chump who doesn’t understand how air power works in the modern era. After all, the most potent threats on the horizon come from China and, to a lesser extent, Russia–both nations with advanced air defense capabilities that would make even the most capable fourth-generation fighters like the new F-15EX a pretty easy target.

The F-15EX is, quite literally, the fastest aircraft in Uncle Sam’s operational inventory, so one could argue that speed just isn’t what combat aviation is about anymore. In fact, that’s exactly what you’ll hear from most fighter pilots today. The F-35, for all its faults, is widely touted as perhaps the most capable tactical aircraft in history, despite being almost slow compared to Cold War powerhouses like the F-14 Tomcat. The F-35A can achieve speeds as high as Mach 1.6, while the F-35B and C are both limited to Mach 1.3–a speed they can only maintain for less than one minute. The long-retired Tomcat, on the other hand, could pass Mach 2.3 without breaking much of a sweat.

The truth of the matter is, in a high-end fight with a nation like China, the United States would be better off flying a fleet of slower F-35s than faster (and more easily targeted) F-14s… but that line of thinking isn’t accurate to the reality of America’s simmering conflict with China. Open and conventional war with China is extremely unlikely any time in the relative future, and while America needs to invest in the technology and a force structure that can deter such a fight even further, the Sino-American conflict is more likely to play out like a new Cold War in the decades to come. That means competing in the developing world, rather than in China’s backyard.

Finally, if a large-scale war were to break out, American pilots will need speed to effectively manage individual engagements as the conflict presses on. Sometimes, the best tactical decision a pilot can make is to “bug out,” or escape the area and an opponent’s advantage. That’s where speed, once again, becomes vital to survival.

Competition with China and Russia will take place in the developing world

Immediately after World War II, the United States and Soviet Union found themselves in a decades-long staring match that prompted huge investments in military capability across both nations. The goal was simple: build the platforms you’d need to win the third World War, and that alone may be enough deterrence to prevent it from starting. Both nations built fighters and bombers that could fly ever higher, ever faster, hoping to defeat burgeoning air defenses like the SR-71 could… by simply outrunning any missile you could shoot at it.

Let there be no doubt that this method of deterrence was effective, and in truth, the most potent weapon systems are those you never have to actually employ in order to achieve your geopolitical goals. But the unintentional side effect of developing more powerful nuclear weapons and more capable airpower platforms was an inability for American and Soviet forces to actually engage one another without bringing about the nuclear apocalypse.

In order to avoid that possibility, the United States and Soviet Union turned to partner nations and proxy forces, expanding influence and strategic leverage around the globe through overt diplomacy and covert military action and assistance. In some cases, partner or proxy forces supported by each respective nation would clash, leading to America’s involvement in conflicts like the Vietnam War. Terrible as these conflicts were, they were considered a tolerable alternative to nuclear winter as the world’s two superpowers tip-toed on the line of global conflict.

China, a nation that wields not only nuclear weapons but a vast amount of economic leverage and the largest naval force on the planet, is similarly positioned for a long and drawn-out staring contest with the United States. Not only would such a fight cripple both national militaries, but it would also neuter China’s ongoing plans for expanding its global influence, as well as create chaos throughout the global economy for decades to come.

Related: JUST HOW BIG IS CHINA’S NAVY? BIGGER THAN YOU THINK

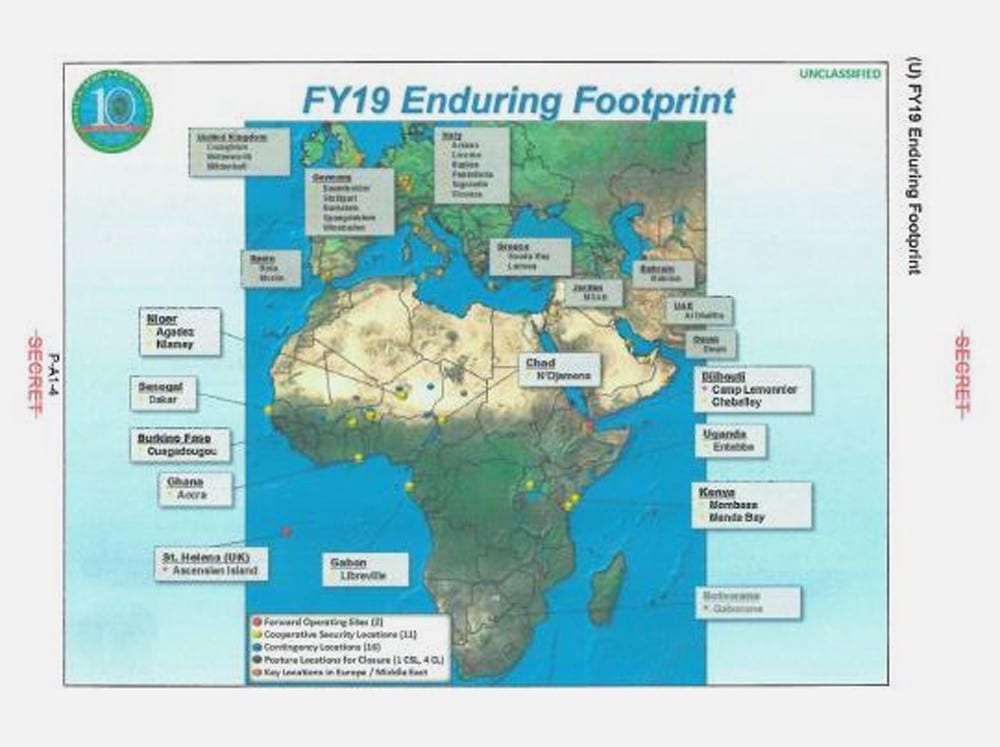

China isn’t going to declare war on the United States any time soon… But China and the United States are going to continue to compete in practically every appreciable way, which includes establishing relationships in developing countries for the purposes of gaining access to strategic resources and ports. As luck (perhaps bad luck) would have it, the regions of the world that are most likely to have those very sorts of commodities on the market throughout the 21st century are often exactly where American and allied forces are already conducting counter violent extremists operations (Counter VEO): Africa and the Middle East.

But while America and its allies have been accumulating operational experience in these theaters, China hasn’t been sleeping. Despite China largely staying out of the Global War on Terror, it has been expanding its influence in these same regions via economic and infrastructure programs, including providing massive loans to developing nations that many suspect won’t be able to pay China back. China, it seems, would prefer they didn’t anyway–as the leverage defaulted loans would offer is more strategically valuable than paying interest on a loan could be.

“Right now you could say that any big project in African cities that is higher than three floors or roads that are longer than three kilometers are most likely being built and engineered by the Chinese. It is ubiquitous,” explained Daan Rogeveen, an author and expert on urbanization in China and Africa.

As a result, there’s an extremely high likelihood that the United States will find itself supporting proxy or partner forces in places like Africa and the Middle East. In fact, America already does. These forces will likely find themselves in direct competition with proxy or partner forces receiving support from China and Russia. The quagmire that is the ongoing conflict in Syria serves as a contemporary example of just how diverse foreign interests within a single nation can be, and just how dangerous operations in one can get.

America’s only dogfight in more than 20 years was in uncontested airspace against a 50-year-old jet

It’s worth noting that it was, in fact, over Syria that the United States scored its only air-to-air kill in literal decades in 2017, when a U.S. Navy F/A-18 Super Hornet was forced to engage a Syrian Air Force Su-22 Fitter that was attacking partner forces on the ground.

This short fight also offered an important lesson about bridging the gap between longstanding airpower and the cutting-edge systems employed by the United States. Lt. Cmdr. Michael Tremel, the pilot in the Super Hornet, first locked onto the Soviet-era Su-22 with the one of the Navy’s latest and most advanced air-to-air weapons, the AIM-9X, but when he fired, the Fitter deployed flares and managed to fool what was previously considered to be the most capable air combat missile in service.

“It came off the rails quick,” Tremel said. “I lost the smoke trail and I had no idea what happened to the missile after that.”

Related: AIR FORCE’S NEW F-15EX MAKES DOGFIGHTING DEBUT IN ALASKA WAR GAMES

Tremel then locked on once again with an older AIM-120 AMRAAM and fired, this time finding his target and turning the Su-22 into a fireball. While the Pentagon hasn’t offered an explanation as to why their newest missile failed to discern a real fighter from a bucket of flares, some experts have postulated that it may have been a result of the AIM-9X being too well-tuned to distinguish jets from the latest and most advanced flares employed by top-of-the-line 4th and 5th generation platforms. The Su-22 has been flying since 1966, and its dirty old flares weren’t something the AIM-9X expected to run into.

Sometimes, winning a fight isn’t about who fields the latest or most expensive technology. It’s about who fields the right technology for the right situation.

Detection isn’t a threat over the developing world. Distance is.

On October 4, 2017, a group of U.S. Army Green Berets and Nigerian soldiers was ambushed by fighters from the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) in Niger. The tragic firefight ended with four dead U.S. troops, five dead Nigerian soldiers, and some difficult questions about how the most highly trained warfighters in the world with support from the most powerful military in the world found themselves fighting through a tactical disadvantage without any air support close enough to make a difference.