Column: Del Mar man made a world-changing phone call 50 years ago

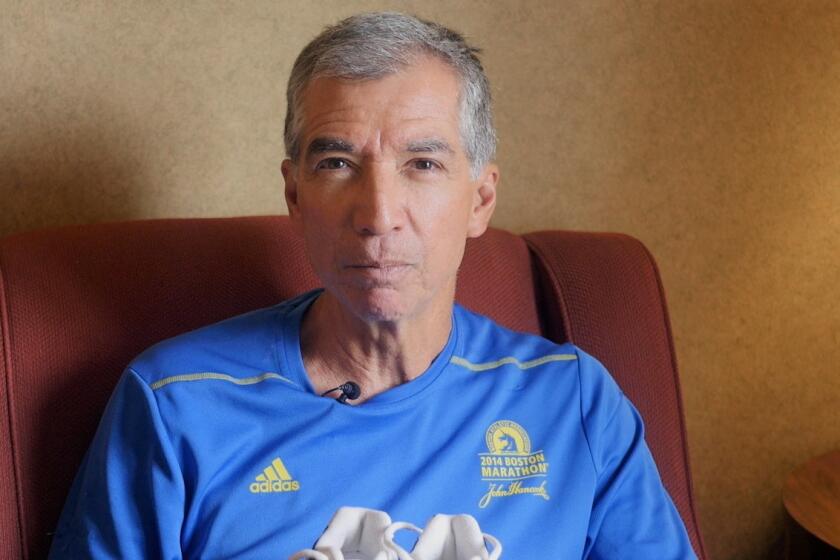

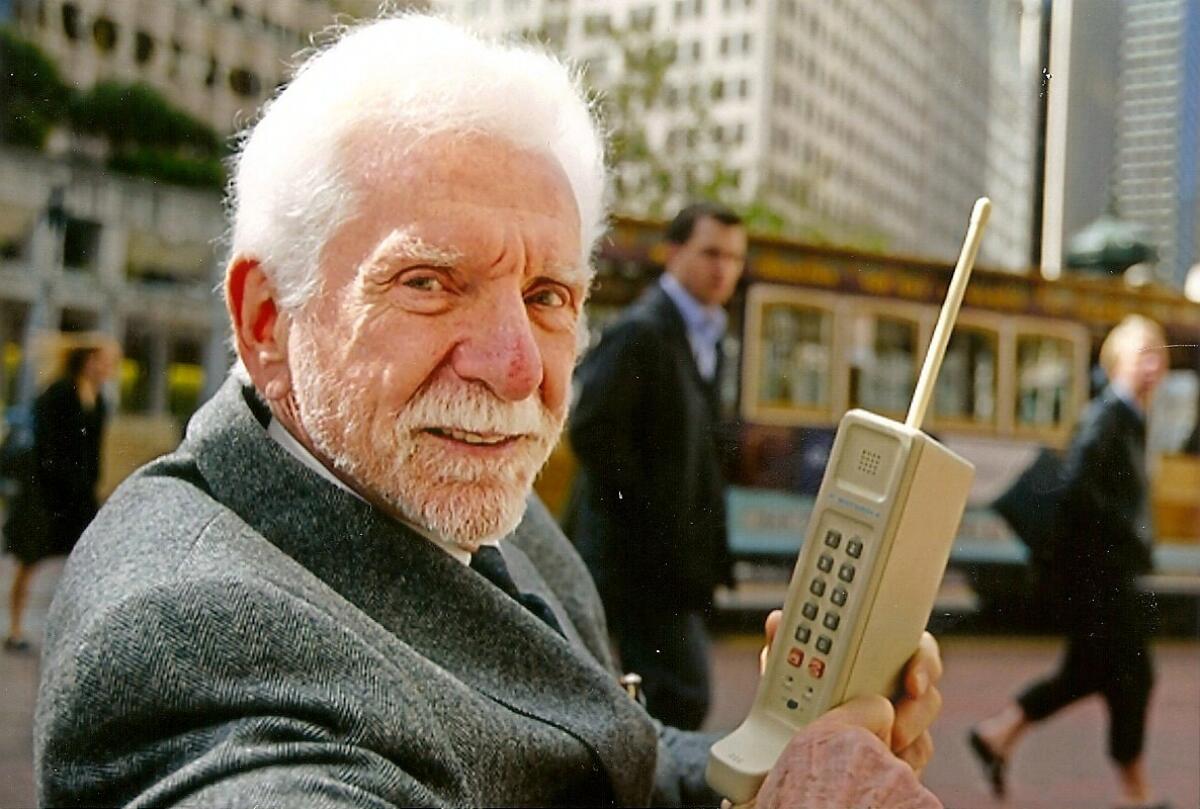

On April 3, Del Mar’s Martin “Marty” Cooper will be in midtown Manhattan reliving his historic first call on a hand-held mobile phone that he and his team designed for Motorola and debuted to the public on April 3, 1973 — 50 years ago.

He had planned to introduce the phone on a major network news show that morning. But, after being “bumped” from the show lineup early in the day, he rendezvoused with a radio reporter on Sixth Avenue in front of the New York Midtown Hilton hotel near West 54th Street.

When invited to demonstrate, Cooper fished a phone number from his pocket for Joel Engel, then head of rival technology at Bell Labs, and notified his competitor that he was being called from a portable phone.

Additional history almost was made that day because Cooper was so engrossed in walking the talk to display the mobility of his invention, that he stepped into the path of a NYC taxi. Luckily, his interviewer yanked him back, out of harm’s way.

On Monday, he’ll re-enact that technological triumph (minus the taxi) with a Wall Street Journal reporter using a non-working prototype of the 2.5-pound phone. NBC’s “Today” show also plans to air a visit to the historic site.

Replicas of the clunky first cellphone are in the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C., and a few museum exhibits around the world, including a temporary display in Balboa Park’s Reuben H. Fleet Science Center.

During a media conference at the Hilton hotel that afternoon in 1973, a young reporter asked if she could use the phone to call her mom in Australia.

“Her mother answered in the middle of the night, and everybody thought it was absolutely amazing,” Cooper chuckles, noting that she didn’t realize the signal was being picked up by a base station across the street which relayed the signal by wire to Australia.

A plaque commemorating the media event was on display for years in the Hilton hotel.

Interestingly, that historic call did not make Cooper a millionaire. “When I joined Motorola, they gave me $1 for all future inventions,” notes the entrepreneurial engineer, who remains happy with that deal.

“Motorola treated me very well. I had the opportunity to make all these inventions, so I thought it was a great company.”

Cooper, who has been dubbed “the father of the cellphone,” is amused at all the hoopla about this half-century anniversary of his first public mobile phone call. “It took 50 years for people to realize how important it was,” he laughs.

If Motorola hadn’t debuted this invention in 1973, Cooper believes it could have taken another 20 years for cellphones to have been utilized by the public because the leading rival device was Bell Labs’ mobile phone for cars. Cell sites would have been built to serve phones in vehicles, not hand-held portable phones, he explains.

This is only one of a string of communications-related inventions given life by Cooper, many before and after his long career with Motorola.

- He introduced two-way radio pagers that catered to law enforcement, fire departments and airport personnel.

- In the mid-1960s, he developed a system for the Chicago Police Department that enabled officers to get out of their patrol cars and use their pagers hands-free via a mike and antenna attached to the shoulder of their uniform.

- In 1963, he developed the first nationwide mobile car telephone system (Improved Mobile Telephone System).

- He designed telephone communications for use in rural areas where wired phones didn’t yet exist.

- Cooper engineered a traffic light control system that harnessed radio waves to adjust traffic signal changes to maximize traffic flow.

- In 1992, Cooper co-founded Arraycomm, which develops software for mobile antennas and related technologies. It became a world leader in smart antenna development.

“I have 11 patents,” says Cooper, whose wife, Arlene Harris, also is an inventor who pioneered GreatCall’s simple-to-use Jitterbug phone for seniors (built by Samsung and now owned by Best Buy).

Time magazine named the entrepreneur one of the top 100 inventors in history. In 2021, he published his autobiography, “Cutting the Cord,” dedicated to his wife.

As important as the cellphone is, Cooper doesn’t consider it his most interesting work. That superlative applies to “Cooper’s Law” of 1992, otherwise known as the Law of Spectral Efficiency.

“You’ll never run out of capacity,” Cooper theorized, because technology and engineers will keep increasing radio spectrum capacity. “Since (Guglielmo) Marconi commercialized radio, capacity of radio spectrum has doubled every 30 months,” he notes.

Cooper’s goal is achieving connectivity across the world for the good of humanity. Thus, his emphasis has been on putting phones in the hands of people, not just in cars or facilities or homes.

The reason the April 3 demonstration was so important to him was because rival Bell system was developing a car telephone, rather than a hand-held phone. “The real need for people was freedom to make calls everywhere,” Coopers says.

Motorola was worried that the much larger Bell system would win the favor of government officials who designate approved signal carriers because it was the dominant, most powerful company at the time.

“I thought, ‘We’ve got to do a dazzling demonstration,’” says Cooper. He did, and a few years later he tried to get the Federal Communications Commission to act more quickly by demonstrating the mobile phone to then Vice President George H.W. Bush, who showed it to President Ronald Reagan, both of whom called their wives on the device.

“The FCC hadn’t made a decision yet,” Cooper recalls, “and Reagan said to George, would you take care of this?”

Cooper’s curiosity was evident at an early age. “From age 5 on, I was taking things apart and trying to figure out why everything worked ... I still take things apart.”

I asked if he had dissected a modern cellphone. “Of course, I’ve taken one apart, and when I put it together it didn’t work.”

Cooper laughingly says his proclivity for fixing things comes in handy at the couple’s home overlooking the ocean in Del Mar where corrosion is a constant companion.

He frequently gets outside for quiet walks on the beach and hikes in a nearby canyon, but when he returns to his home office, he truly is connected. He faces a huge screen with multiple images and converses online to people around the world.

Today he serves on the FCC advisory council of industry volunteers who advise the agency on how to solve some of today’s transmission issues.

Cooper is convinced that expanding cellphone use will help revolutionize education and eliminate disease. Rather than increasingly fast, more powerful technology such as 5G, he prefers working to broaden the global reach of communication, keeping the cost low and getting a cellphone in everyone’s hand.

In 1973 when he made that first call, there were no hand-held cellphones. Now 8 billion cellphones are in use, and two-thirds of the people in the world have access to one. Now that is something to celebrate.

Get Essential San Diego, weekday mornings

Get top headlines from the Union-Tribune in your inbox weekday mornings, including top news, local, sports, business, entertainment and opinion.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the San Diego Union-Tribune.