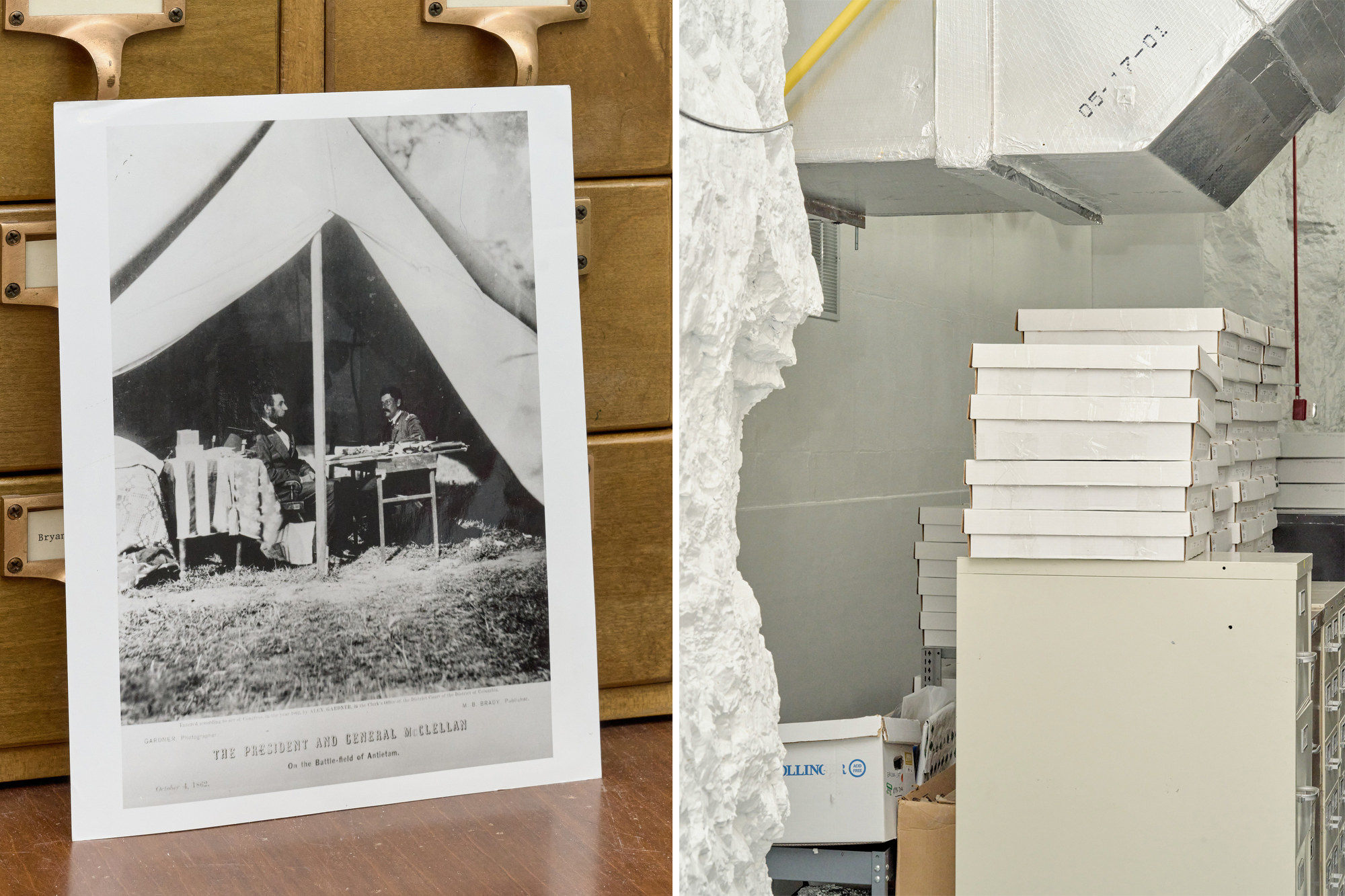

If you travel about 51 miles north of Pittsburgh and go 220 feet underground, past armed guards, you’ll find the Bettmann Archive. If you’re somewhat familiar with the world of photojournalism, there’s a good chance you’ve heard of this renowned archive that's managed by Getty Images. Preserving around 11 million images, the archive is a visual record of many of the world’s most important historical events since the invention of the camera in the early 1800s.

The Bettmann Archive was started by Otto Bettmann, a curator living in Nazi-occupied Germany, where he worked as the curator of rare books at the Prussian State Art Library in Berlin. Known to many as “The Picture Man,” Bettmann was dismissed from his position after Adolf Hitler took power and forced Jewish people out of civil service jobs. When he fled Germany for the United States in 1935, Bettmann “virtually invented the image resource business,” according to the archive’s former owner and now-defunct image licensing giant Corbis. When he arrived, he had just two trunks filled with old photo prints, which is what humbly began the now-vast archive that still bears his name.

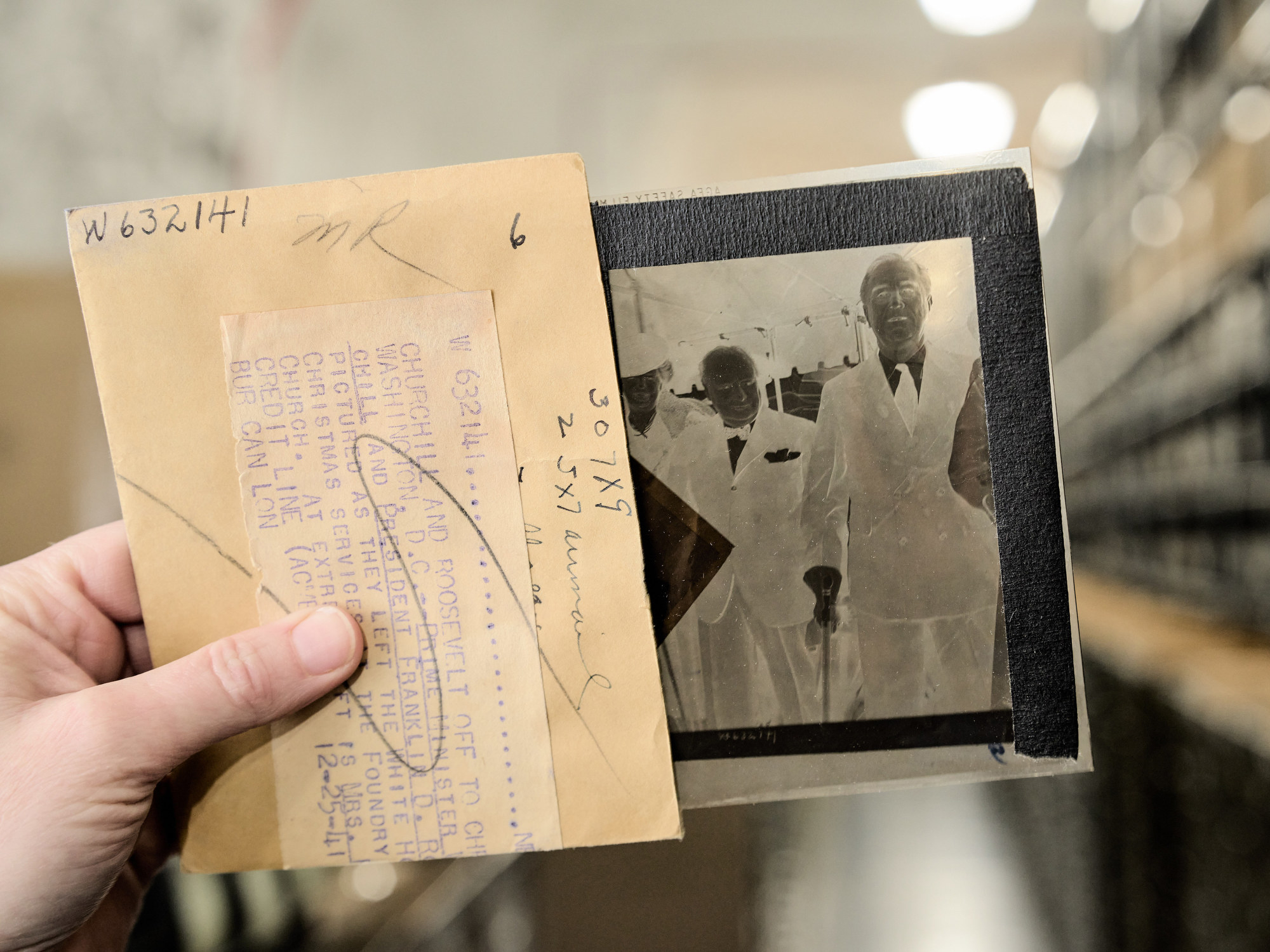

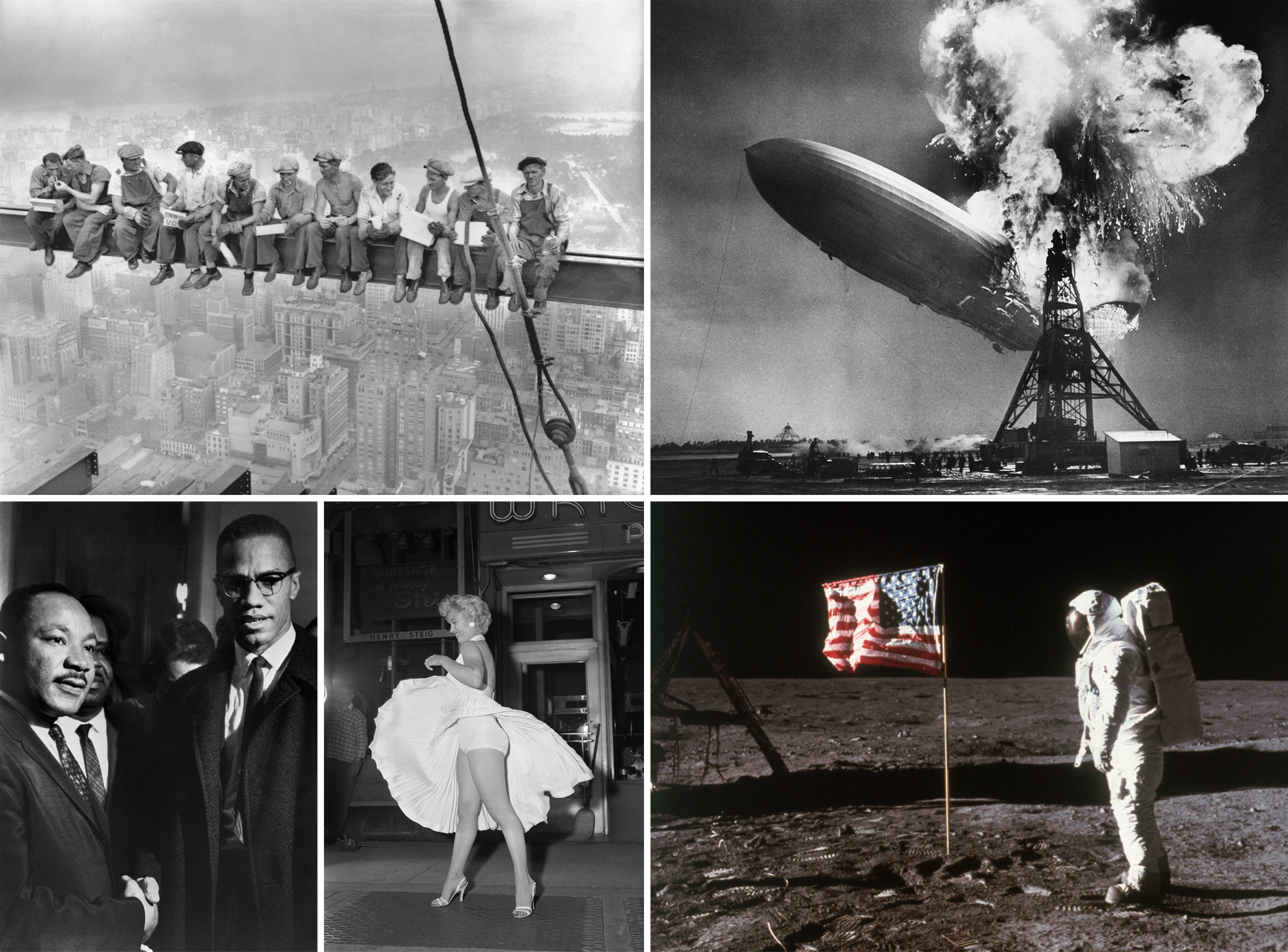

Over the next few decades, with his encyclopedic knowledge of historical visuals, Bettmann figured out a cunning business, licensing images he amassed to editorial and advertising clients. Charles Clyde Ebbets’s “Lunch Atop a Skyscraper,” the Apollo 11 moon landing, Malcolm X meeting Martin Luther King Jr., the Hindenburg’s explosion, and a young Queen Elizabeth II (posing with one of her corgis) is only a small taste of the archive’s famous images.

When he was 78, he spoke of his relationship with clients, telling the New York Times, “Instead of visual cliches, I provided them with a graphic shorthand that illuminates the present by revealing the past, preferably with humor.”

In 1981, the archive, which by this point had amassed 3 million photos, was acquired by the Kraus Organization, the rights holder for the United Press International Library, which also contained a huge collection of images of 20th-century news photographs. The Corbis Corporation, a popular image-licensing company formerly owned by Bill Gates, purchased this sprawling collection in 1995. Up to that point, the Bettmann Archive was located in New York City, however, the weather conditions there over time caused deterioration of the acetate negatives.

Between summer 2001 and March 2002, Corbis, with the assistance of archival expert Henry Wilhelm, moved the entire archive’s contents from New York to a new home in an underground facility in the Iron Mountain near Boyers, Pennsylvania. The vault, which is part of a series of former limestone mines, is both temperature- and moisture-controlled. These careful conditions have virtually stopped the degradation of the photographic negatives.

BuzzFeed News spoke with Leslie Stauffer and Sarah Kubiak, the Bettmann Archive’s sole archivists, about the day-to-day of their fascinating jobs and what it’s like to work in an extremely secure vault that’s like something out of a movie, all while surrounded by a priceless collection of images.

Can you talk a little bit about the archive’s security measures and why this is a thing?

Sarah Kubiak: The Bettmann is housed in a high-security facility. Iron Mountain bought the defunct limestone mine from US Steel and created vaults for many other private businesses and government agencies. Their safety measures ensure the protection of all their clients’ assets. Every day when we enter the mine, our cars, belongings, and persons are searched similarly to TSA. The archive is located 220 feet underground and is the furthest business within the facility. The mine is made up of “streets” that have unmarked doors hiding all the treasures inside. The Bettmann collection is stored in an airlock-protected vault that is 38 to 42 degrees Fahrenheit and 40% humidity.

How did you come to be involved in working with the Bettmann Archive and when?

Leslie Stauffer: We both started working at the Bettmann Archive as Slippery Rock University graduate student interns in 2004. We were later hired by the Corbis Corporation as full-time employees. In 2016, Corbis was sold to Visual China Group (VCG) with a distribution partnership with Getty Images. Getty Images hired us to run the day-to-day business of the Bettmann.

What does a typical workday for you look like at the archive?

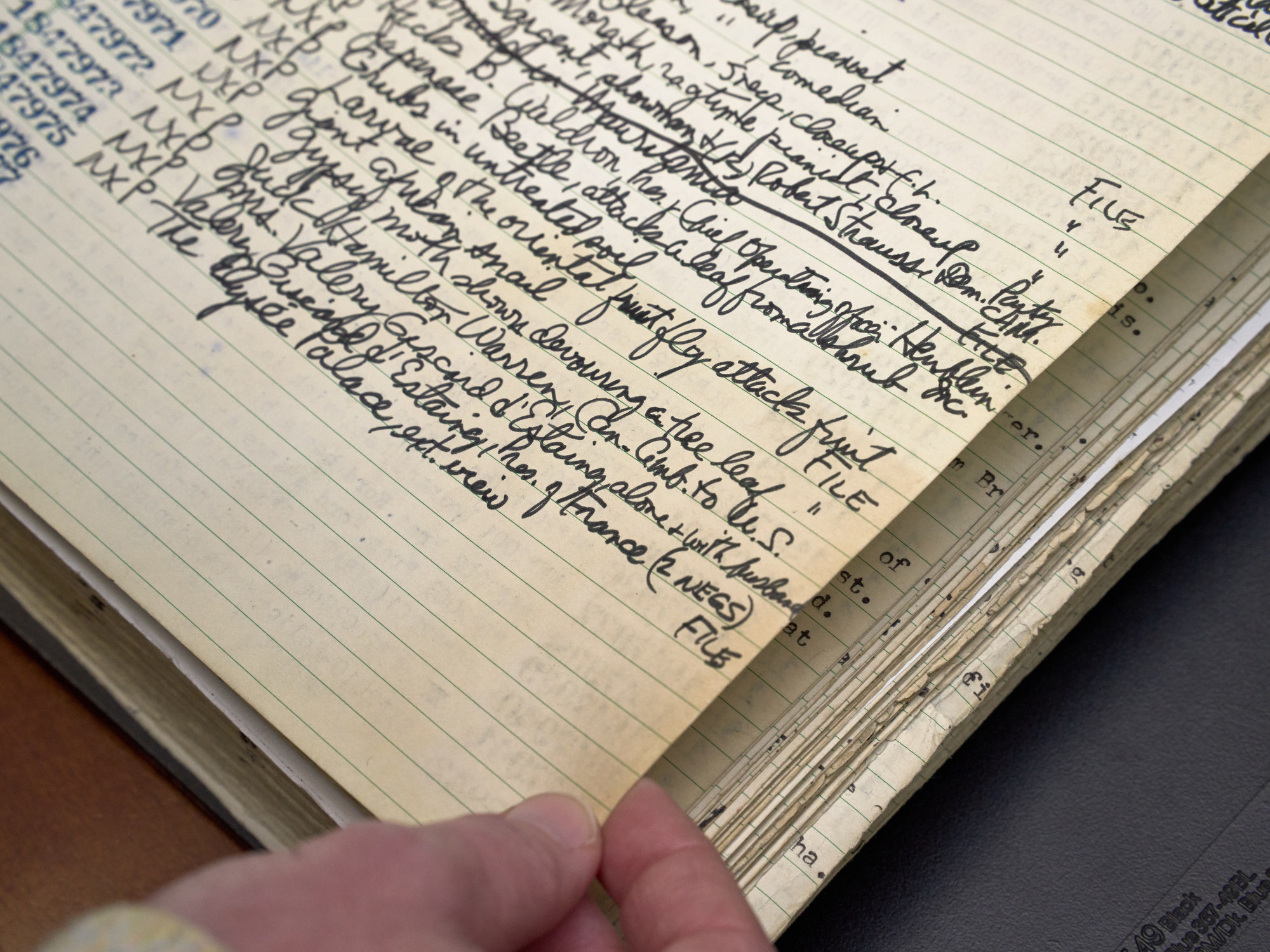

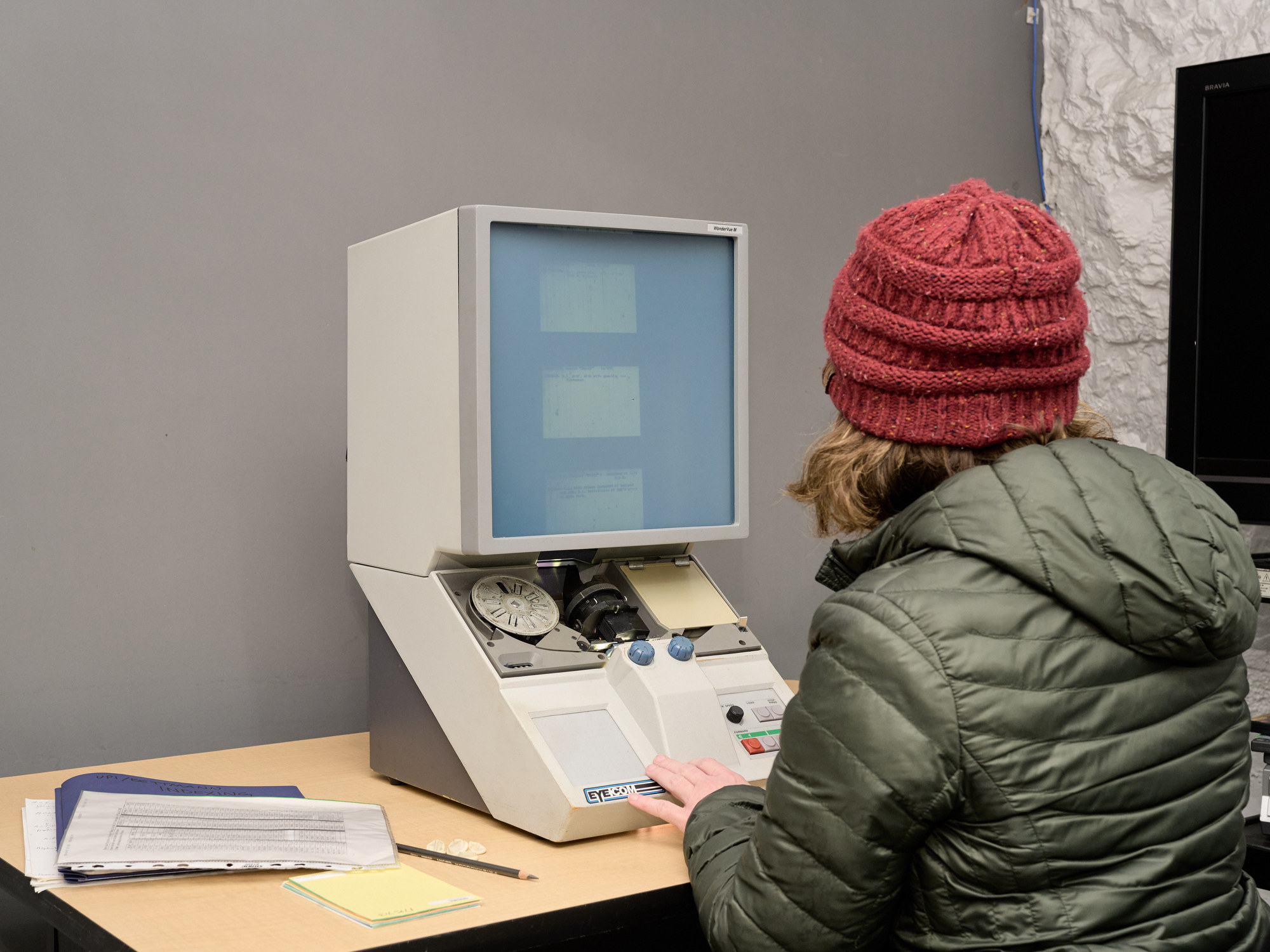

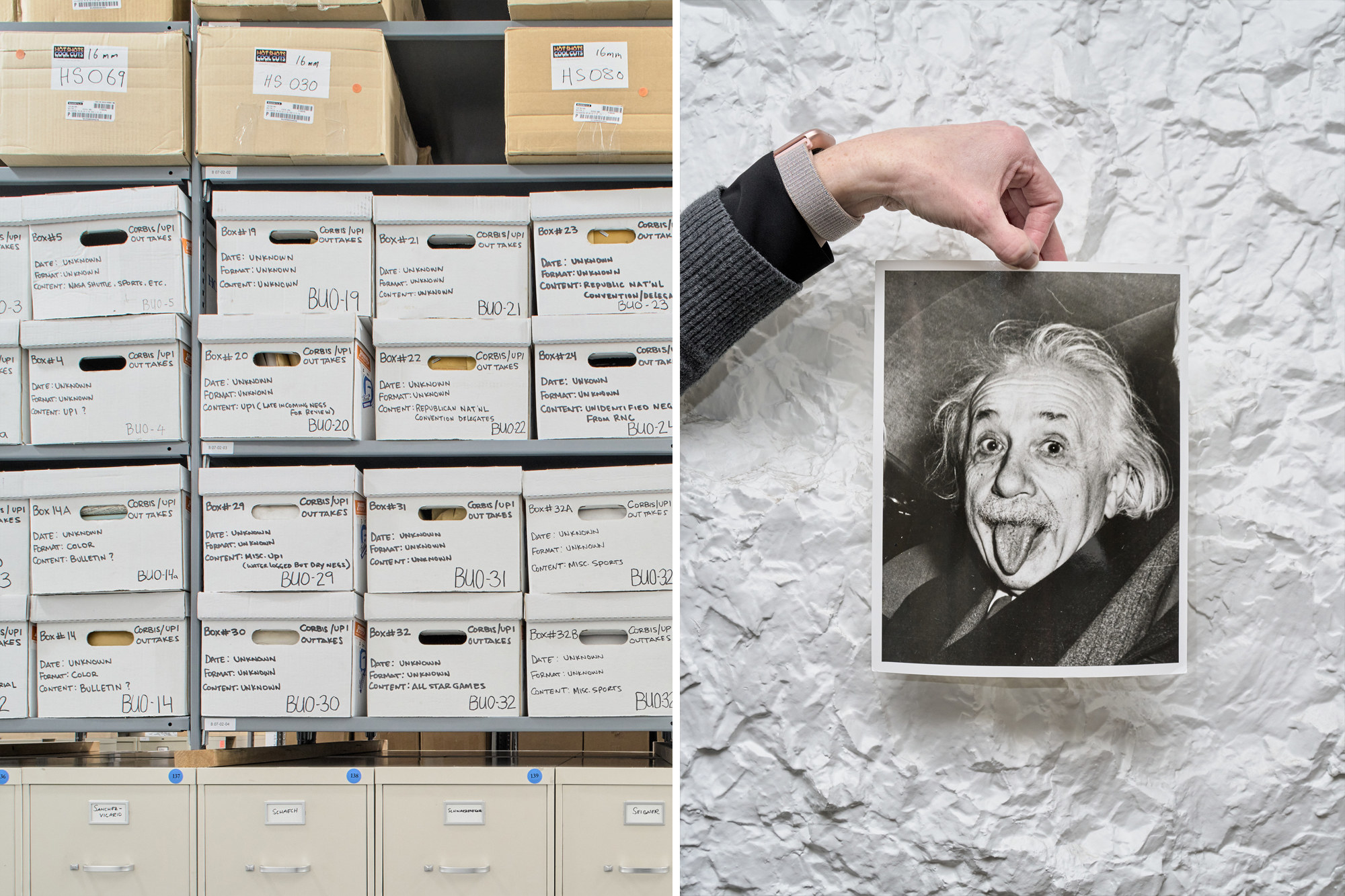

SK: Each day at the Bettmann Archive looks a little different. The physical labor of pulling, scanning, and filing the images has become rote after 18 years; however, we are never bored with our research and what we find in the collection. The collections are well organized utilizing several types of finding aids. We use print files, analog card catalogs, microfilm, and logbooks that list the images numerically by collection. Each collection has its own unique language of image identification.

It has taken years of research to know exactly where to look and if one of us is confounded by their search the other usually has an answer. We complete research requests for customers’ projects: documentaries, book publishers, and news outlets. We complete the entire process of research, digitization, adding metadata, and uploading images to the online photo library on gettyimages.com. We also conduct proactive research based on current events to see if we have any related content hiding in the archive.

How large is the staff at the archive?

LS: There are two archivists that staff the Bettmann Archive. We have worked together for nearly two decades spending more time with each other than our families. We both manage the day-to-day responsibilities for the collection and the facility. It is a unique place to work. To protect the collection, the office has no running water. The bathrooms are located a couple of “streets” away. The facility is in rural western Pennsylvania without the convenience of restaurants. If we did have food options, we would need to drive out of the mine and then go back through security to enter again. So, every day we bring in our own food and water.

Can you talk a little about the archiving process, film degradation, and why this process is important?

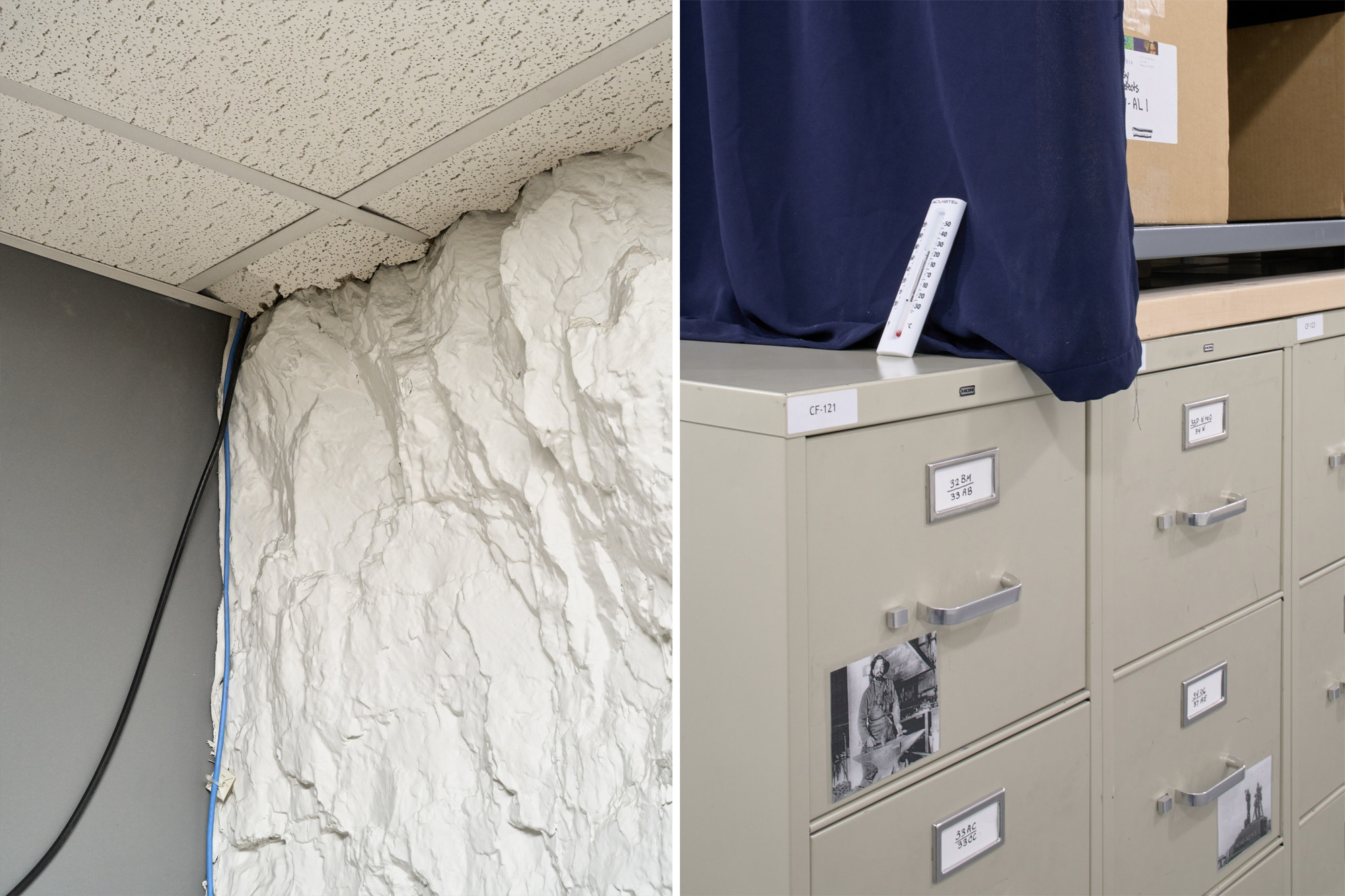

SK: As archivists, we work to preserve the photo negatives and make them accessible to the public. Film degradation was one of the major reasons the Bettmann Archive collections were moved to the underground storage facility at Iron Mountain. Our vault space is temperature- and humidity-regulated, and the film degradation has stopped occurring in that environment. The entire office is 10,000 square feet, half of which is under refrigeration. Our scanning lab has a flatbed scanner for glass plates and damaged acetate 4x5 negatives and a Hasselblad Flextight for 35mm film. By digitizing analog imagery, we provide a way for the public to interact with historical events that were, in some instances, unseen since they were filed into the collections.

What has been your biggest challenge working in the Bettmann Archive?

SK: I would say the biggest challenge is working in the physical environment of the underground mine. Our archive vault is temperature regulated at 42–38 degrees Fahrenheit and there are no windows.

LS: I agree the physical environment is the biggest challenge. Spending all day underground while enjoying the work is difficult. In the winter, we don’t see the sun until the weekend. We enter when it’s dark and leave when it’s dark. When I drive in, there are always people walking around for exercise. It really is a little city down here.

What’s the most rewarding aspect of working in the archive?

SK: Being able to provide our clients with imagery that specifically meets their needs so they can tell their stories in a unique and differentiated manner is the most rewarding part of the job for me.

LS: I had no intention of a career in library science. I was a corporate trainer and recruiter in Colorado for a few years and wanted a change. I moved to my mom’s hometown to live with my grandma and applied to graduate school for history. Dr. David Dixon gave me the internship opportunity and the rest is history, as they say. I see part of my job as a sort of history activist. We provide the photographic evidence of historical facts. Making the historical photography contained in the archive accessible to the public is what’s rewarding. We find content that reflects the times and illustrates the aphorism that history does repeat itself.

Do you ever discover images you didn’t realize were in the archive?

SK: The Bettmann Archive is filled with news photography collections; they cover a breadth and depth of topics. It is always exciting to find that one specific image that a client is seeking out, and I love knowing that we are the only archive that may have that one special frame they want.

LS: The Bettmann Archive houses and preserves 11 million images. Only 250,000-plus images have been digitized and uploaded to the Getty Images site. There is never an end to what we may discover. We love to hunt for client specifics, but it is incredibly satisfying to locate an undeniable gem.

What is your favorite photo in the collection?

SK: I don’t have a favorite photo. I look at so many images daily that it would be impossible for me to choose just one, but I am drawn to the imagery of the 1930s and 1940s.

LS: My favorite photo changes continually. We have an incredible amount of WWI, WWII, and Vietnam War photography. We have imagery taken by Kirochi Sawada who won the Pulitzer for his Vietnam war photography. David Hume Kennerly shot imagery for UPI and was a Pulitzer winner. We have binders of photos taken by brothers Peter and David Turnley. David has also won the Pulitzer for his imagery. I have looked at tens of thousands of images while working at the Bettmann, picking one is an impossible task.

What have you learned from this job?

SK: Working in an underground facility presents many challenges. We are 220 feet underground and are the last business, nearly a half mile, in the back of a mine. For example, if there are connectivity issues, we have to drive outside to use our cellphones and ask for assistance. If we need something repaired, we need 48 hours’ notice for security notification before a visitor can enter the mine. We have become incredibly skilled at problem-solving. We are committed to making sure our customers receive their imagery regardless of the issues at the archive.

What do you hope other people take away from learning about the archive?

SK: Despite its location in the underground facility, the Bettmann Archive is accessible to anyone through gettyimages.com, as well as by request through the sales team.

LS: Most people are unaware of the Bettmann Archive and what it contains in general. My dad was shocked when he visited. He ended up looking at WWII photography for two entire days. Anyone who visits has their mind blown. We are always looking for opportunities to present the incredible history preserved underground. I can’t imagine doing anything else.