In 1880s San Francisco, Abby Fisher's pronounced Southern accent must have been difficult to decipher. When the South Carolina–born cook dictated her recipes to friends, the word "succotash" ended up transcribed on the page as "circuit hash." The recipe itself—slow-cooked tomatoes, butter beans, corn, and pork—makes plain what Fisher meant.

At that point in her life, Fisher, in her late 40s and mother to 11 children, was selling foodstuffs from a shop on Howard Street. Most famous for her pickles, jellies, and preserves, she garnered top medals at state fairs—and enough fans to support her in publishing her own cookbook in 1881.

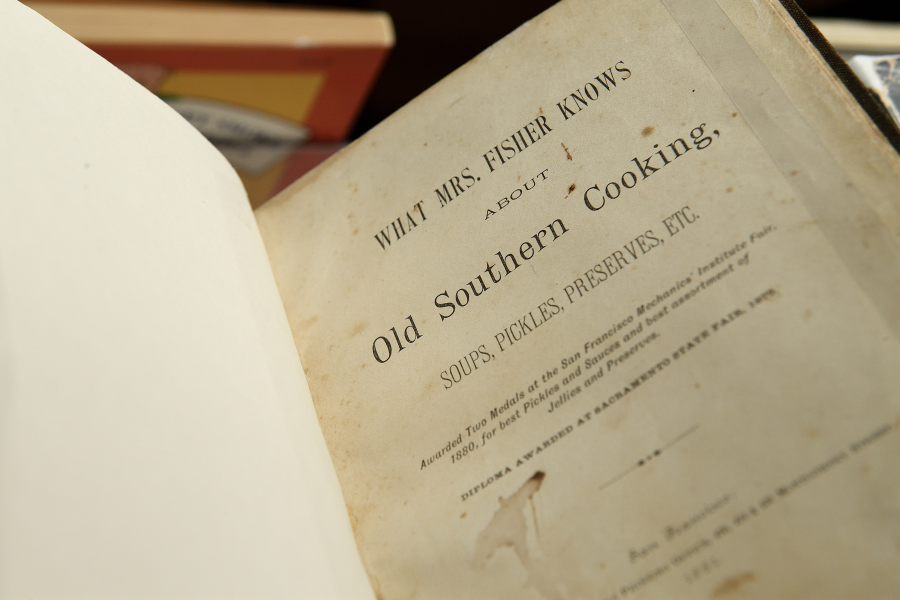

What Mrs. Fisher Knows About Old Southern Cooking was a striking anomaly for its time. Fisher was not only a woman but a Black woman, believed to be born into slavery. Somehow, she had fled the post–Civil War South, traversed the country to reach California, and through her cooking made a name and livelihood for herself. Unable to read or write, she talked through 160 recipes—flavorful stews, gumbos, roasted meats, biscuits, pies, jams, and more—to be set to paper. Today, her cookbook is recognized as being only the second one authored by a Black woman in the United States.

Fascinated by the story, Johns Hopkins University librarian Heidi Herr spent several years trying to track down a first-edition copy of What Mrs. Fisher Knows, finally succeeding in 2020. JHU conservators worked to resew the binding and restore the cover, making the delicate book available for research and exhibition purposes.

"Finding out about Abby Fisher was incredible, in part because her legacy was forgotten for so long," says Herr, who has collected many historical cookbooks for the Special Collections at Sheridan Libraries and taught a course called Cooks and Their Books. "Her cookbook was only rediscovered in the 1980s, and since then a lot of information has come out about her life and also the legacy of other forgotten African American cookbook authors."

What Mrs. Fisher Knows was recently featured in a Sheridan Libraries exhibit alongside The New Orleans Cookbook by Lena Richard (1940) and A Date With a Dish (1948) by then Ebony food editor Frida DeKnight. Herr says the library is also working to acquire the cookbook that predates Fisher's as the first in the U.S. by a Black woman: Malinda Russell's A Domestic Cookbook: Containing a Careful Selection of Useful Receipts for the Kitchen (1866)—also thought to be the first Black-authored cookbook, period.

Fisher's book was discovered years before Russell's, becoming an item of fascination when it came up for auction at Sotheby's in 1984. A decade later, the small firm Applewood Books located one of the rare copies and reprinted it, with an afterword by food historian Karen Hess piecing together Fisher's biography through historical records.

The 1880 census lists Abby C. Fisher, age 48, living at 207 ½ Second Street in San Francisco with her husband, Alexander, her profession named as "cook" and her race as "mu," meaning mulatto. Documents show that Fisher's mother was from South Carolina and her father from France—a heritage that makes slavery a safe assumption, Hess concluded.

Fisher's husband is also listed as mulatto, born in Alabama, where three of the couple's children were also born. It's baffling to imagine how the family made its way from there to California in the years following the Civil War, when train travel was prohibitively expensive. By 1880, San Francisco directories show "Mrs. Abby Fisher & Co." listed at 569 Howard St. selling "pickles, preserves, brandies, fruits, etc." In the census, her husband is listed as a pickle and preserve manufacturer, presumably aiding his wife.

Also see

To publish her cookbook the following year, Fisher and her supporters turned to the Women's Cooperative Printing Union, another rarity of its time as a female-owned business. Fisher's recipes—based on "upwards of third-five years" in the art of Southern cooking, she says in her preface—include terrapin stew, sweet watermelon rind pickle, stuffed eggplant, roasted quail, green turtle soup, brandied peach preserves, oyster gumbo, and eight varieties of croquettes. Her instructions lack fuss, intended to be easy enough that even a child can follow. Here's fried chicken, for example: "Have your fat very hot, and drop pieces into it, and let them cook brown. The chicken is done when the fork passes easily into it."

As Hess noted, Abby Fisher's recipes help underscore the imprint that Black female cooks, particularly enslaved women, made on Southern cooking. The region's cuisine, she wrote, was "transfigured by the genius, indeed the very presence, of … women cooks in the kitchens of wealthy slaveowners."

The copy of What Mrs. Fisher Knows that landed at Johns Hopkins shows signs of years of heavy use, smears of oil and food splattered throughout its pages. "When it comes to cookbooks, I honestly don't mind if they show wear and tear, especially with a book like Mrs. Fisher's," Herr says. "That suggests this book was truly cherished and used constantly, maybe by several members of a family over the decades. To me, that just adds so much warmth and interest."

Posted in Arts+Culture

Tagged sheridan libraries, food, special collections, cooking, cookbook, black history